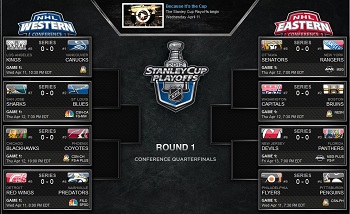

Iggy’s Picks for Round 1 of the 2012 Stanley Cup Playoffs

I want to thank all our Fans for their support and help in growing out HOHM this hockey season. As someone who has a great deal of passion for the game and every team, it has been a pleasure to connect with many of you and talk hockey! It also will pain me to express my judgements in talking about the potential elimination of your team in the first round. These are just my opinions and something I have been doing for the past few years with friends for fun and to make watching the playoffs that much more exciting. I wish all 16 teams the best of luck in the playoffs and again to all our fans, thank you for your passionate support!

For the last 3 years I have gone 7 of 8 in the first round with my picks amongst my friends. However when I sat down to make my picks for this year’s playoffs….I found myself heartbroken. This was the first time in my picks that even after expressing my judgements/opinions…I am still not 100% certain as I have been in the past. I don’t expect to go 7 of 8 this year because of the amazing matchups and the real potential for every series to go either way. So here are my conclusions anyway……

Eastern Conference

(1) New York Rangers vs. (8) Ottawa Senators

Both teams have shared success this year. However, the Senators ended their season on a 3 game slump and although they will be avoiding playing the Bruins, the Rangers are in every fashion similar. This should be the least likely series for an upset but I do see the Senators prolonging this series past a potential sweep talk. Look for a 5 to 6 game series at the most before this one is all said and done.

Prediction: New York

(2) Boston Bruins vs. (7) Washington Capitals

The Bruins have been a very strong team all year despite many late season hiccups. Tim Thomas anchors the team in net with Chara holding down the defense and great young forwards edging the team’s offensive depth. While the Capitals might have a slight advantage in the offensive talent department over the Bruins, they are unfortunately dealing with two injured starting goalies. The real question will lie if Holtbly can rise to the occasion and if the inconsistent play of the Capitals will find a rhythm. Still I favor the Bruins to take this series; they didn’t play hard all year for an early exit. Look for the Capitals to push this series 6 games with only a likely hood of a 7th if they can clamp down their defensive game.

Prediction: Boston

(3) Florida Panthers vs. (6) New Jersey Devils

It truly is nice to see the Panthers reach the playoffs after a 12 year drought, especially with them edging out and winning the southeast division. However that is as far as this story will go for the Panthers for the 2011-2012 season. The Devils are a better team and this is my only matchup that I see a potential sweep occurring. Can the Panthers upset the Devils? Plausible but not very likely even with the recent years of bad luck for the Devils in the first round. The Devils will wrap this up in 4 to 5 games.

Prediction: New Jersey

(4) Pittsburgh Penguins vs. (5) Philadelphia Flyers

In my eyes this is the most anticipated series of the east for the first round of the playoffs. Truly this series can go either way. Both teams have talent, experience, but the what I feel will be the biggest deciding factor is which team will be the most physical and disciplined. I would be disappointed to see this series go any less than at least 6 games but see it going the full distance with the Flyers coming out on top as long as they stick to their regular season dominating ways of the Pens.

Prediction: Philadelphia

Western Conference

(1) Vancouver Canucks vs. (8) Los Angeles Kings

Many are picking the Canucks to be the obvious winner of this series. Although I agree, I am more than certain that Quick will be the very X factor of this entire series. Quick can steal a game for the Kings even with their major issues of finding the back of the net often. However the Canucks are just too good of a team to go down in the first round. This is a team that is still incredibly hungry for their first ever Stanley Cup. Look for this series to go 5 or 6 games at most with Vancouver eyeing a 2nd round matchup.

Prediction: Vancouver

(2) St. Louis Blues vs. (7) San Jose Sharks

Two surprises from this very series. The first being the amazing season the Blues have put together and the other being the awful second half and of a season the Sharks ended up having. Not only were the Blues incredibly dominate in the regular season against the Sharks (4-0-0) but the Blues are no team to take lightly. Now, this won’t be the easiest series for the Blues but I don’t expect the Sharks to push this to more than 6 games if at all 5.

Prediction: St. Louis

(3) Phoenix Coyotes vs. (6) Chicago Blackhawks

The Coyotes are for real. Three seasons now with 40 or more wins including their first ever division title. This isn’t just a team relying on Smith but a team with a solid mix of defense and offensive threat. The Blackhawks are still without their captain, Jonathan Toews, and although they have more playoff experience, it won’t be nearly the advantage that many might think it is. This is the year that the Coyotes win their first ever playoff series and shock the many still to be disbelievers out there. Look for this series to go at least 6 games.

Prediction: Phoenix

(4) Nashville Predators vs. (5) Detroit Red Wings

Again, in my eyes this is the most anticipated series of the west. Both teams not only went 3-3-0 against each other but finished just about identical to one another. However the Red Wings hold an advantage every time they play on their home ice. The Predators hold the actual home ice advantage in the series. So how do I truly pick one team over the other? Just like the Flyers and Pens series, I would be disappointed to not see this go at least 6 games with the very likely hood of it going the full distance to a game 7. In the end, Nashville will make their second straight second round appearance.

Prediction: Nashville

There you have it. You may Agree or disagree with me, but that is just how I see the first round will shape up this year. I would love to talk hockey with all of you throughout the playoffs. Please feel more than free to reach me by Facebook with a friend request: http://www.facebook.com/igor.burdetskiy

Here’s to hockey!

PS: I will be having the HOHM staff put in their picks on each playoff series as well. I am pretty curious to see what they think!